The power and the water have been on and off all week. After the water went out for the first time, I started keeping a full bucket in the bathroom. But when the power goes off, it’s just a minor inconvenience. I can’t boil water or turn on my fan. No problem. So it wasn’t until last night, when the darkness fell, rapidly, that I really took notice. I was sitting on the balcony, eating my bowl of rice in the waning light. In the time it took me to finish, it became totally dark. Small lights began to go on in the windows of the dorm across from mine. I sat outside in the darkness for a few minutes. The group that stands and chants beneath a nearby tree every night began gathering, their voices slowly swelling.

I went inside to chop the vegetables I’d washed earlier for a salad. I chopped in the dark, slowly. I was thinking about the power outages of my childhood. After a storm, usually. We would light candles and gather together as a family in the living room. Those nights had a sacred quality; the darkness brought us together, the candles making a flickering circle in a cradle of dark. I wondered, as I stood there chopping, if Ghanaians here in Accra gather like that in the candlelight, if there is something special to them about nights without power. Or is it too commonplace?

Thinking of the togetherness of those nights of my childhood, I paused in my chopping. I walked down the dark hallway. It looked endless, like a hall of mirrors stretching into black. I knocked on Sarah and Lesego’s door. I told them to bring their bowls. They brought their light. Sarah made some dressing. I chopped more lettuce, cucumber and tomato. And we ate and we talked and then they left.

I was in Madina market when the power went out. I had just purchased a small used refrigerator, which the owners were cleaning for me. I went to look for a few more things while they finished. After about five minutes, I received a marriage proposal, from a surprisingly well-dressed young man. I laughed and told him I was already married, which is generally the easiest way out of such suggestions. “Second husband!” he said, also laughing. “And second priority!” I shot back. We both laughed and I continued on my way, walking into the heart of the market. I was standing in a cloth shop when the lights went out and the fan stopped whirring.

It was my second time at Madina in two days, and my second trip to a market of the day. I had been to Madina the previous day, Friday, at 6 a.m., on an assignment for my class, Drama in African Societies. The five of us met to observe the real-life dramas at the opening of the market. People lining up to catch tro-tros. A church service. Early-morning transactions. A woman sleeping in her vegetables. A man with a new shipment of used clothes calling out, One cedi! One, one cedi!

We even had a little real-world drama of our own…

Mariama (far left) was taking issue with the fact that Zablong (far right) had reprimanded her earlier for trying to buy fish while we were working, and was now buying women’s clothes. (For his daughter, he told us.) Margaret (next to Zablong) and I were amused, while the guy selling clothes (next to Mariama) just kept trying to sell the clothes.

After we finished our observations, I went to buy a small hotplate. Almost on impulse, I also bought a small battery-powered radio, which, I discovered later, has an LED flashlight (“torch,” they call it, like the British) on the end. It came in handy last night, though the fridge and the hotplate were totally useless. The fridge got up to my room thanks to David, a young man who does odd jobs around the hostel. He saw me getting out of the cab, and came over to help. The fridge went on his head and up the stairs and down the hall to my room. I gave him all the cedis left in my wallet. Which sadly was not many thanks to the fridge and the temptations of the cloth shop.

Then I went to take my sheets off the clothesline outside the building. Some Ghanaians have washing machines, but they’re fairly uncommon, and we don’t have one in or near or building. You can hire someone to do your laundry for you or just do it yourself and hang it out to dry. I’m no stranger to washing clothes by hand, especially after my six months of travel with only a few items of clothing. But every time I mention laundry, the Ghanaians I’m speaking to seem amazed. “By hand?! You know how to do that?” As I was hanging my sheets, two guys who were “having brunch” on their porch at ground level called out to me. They were amused by an obruni doing her very own laundry. “It’s your first time, though, right?” they asked, when I told them it wasn’t so hard. One of them, Raza, told me he can’t do it – laundry, that is – so he bought a washing machine to keep in his room. I told him we were now friends.

But when I went back that afternoon, my sheets were gone. My sweater and t-shirt that I’d also hung out were still there, but the sheet and the matching pillowcase were missing, just the clothespins stuck forlornly to the line. Washing them had taken me two hours and I was looking forward to fresh-smelling, sun-dried sheets. Next time, I’ll have to hire David to keep an eye on them. They were really ugly sheets; whoever stole them has terrible taste!

But the day ended well, with a meal with friends in the dark. And it started well too. I met Mel, one of the other Rotary scholars not long after dawn to run together to Dome market. Both of us are registered for the half-marathon next weekend. It was a great run through a part of the city I haven’t been to before, and we ended at Dome, a charming small market full of fantastic fresh vegetables. That’s where I’d bought the ingredients for my salad. Mel’s really great and very interesting. She served in the Peace Corps in Cape Verde Islands off Senegal several years ago, and her husband came with her here to Ghana. I’m excited to get to know her better, and I hope Saturday morning runs with her become another ritual.

And the day started and ended with music. Music is everywhere here, all the time. At 6:30 in the morning, four boys with guitars came to sing outside the hostel, right below my window. And at night, with the lights out, the praise-singers’ voices and clapping seemed to fill the air more than they usually do.

So, the beginning and the end of my day:

(Folks who get this by email may need to go to the blog to see this link.)

We talked about palanquins in class. I was astonished. Delighted. Real palanquins?! I don’t think I’ve ever had occasion to actually use the word, except when singing along to The Decemberists, so I had to be sure I had the right meaning; “A palanquin is a litter, right?”

Yes, it is. And last weekend, I saw one. More than one, actually. Regina and I went to Fetu Afahye, the big yearly festival of the Fanti people. The festival takes place in Cape Coast (Oguaa in Fante), which is both their main city and the site of the infamous Cape Coast Castle.

The symbolism and ritual significance of festivals in Ghana is rich, and unfortunately much of it is still lost on me. They have a ritual aspect and a public aspect, and the two are intertwined. They reflect and reinforce – but also sometimes invert and mock – the traditional social order, and often span days. Fetu Afahye lasts a week, events and rituals gradually building to a climactic procession on Saturday.

That’s what we went to see.

We got up early, having heard that the procession started at 7:30 a.m. We were informed otherwise by people on the street. So we had some egg sandwiches at Janet’s Spot. They were to die for. And then we explored.

The Main Square in early morning, all decked out with MTN advertising. MTN is a big cellular and internet provider, and they seem to be the dominant advertisers here.

These clowns were everywhere. They would ask for money and then either dance for you or do some stunts. Pretty much everyone would give them a coin or two.

After we’d found a good place to watch the procession, we fortuitously ran into a really nice young man who worked at our hotel. (Actually, there were no rooms available at our hotel, so we stayed in a tent. It was really very nice.) He invited us to join his clan. They were hanging out in a back alley, preparing to join the procession. We shook hands with a couple of chiefs, told the queenmother she was beautiful (she was), and asked lots of questions. Then suddenly we were all pouring out of the alley into the street, where everyone began clapping and singing and dancing.

And then came the palanquins. With spinning elevated umbrellas.

The chiefs in our adopted clan were sub-chiefs, so they walked instead of riding in palanquins. Apparently, at social functions, status disputes sometimes arise in various symbolic acts (like arriving in a palanquin vs. a car) between chiefs; there’s a whole mess of protocol to be observed. That’s what we’d been talking about in class when palanquins first came up.

Each chief has his or her (yes, there are some female chiefs) entourage. Women dancing in front, the chief’s linguist walking seriously with his staff, drummers walking behind.

Part of the entourage. All of the dances, movements, gestures, clothing have significance. I’ll get into that later, as far as I’m capable.

There were all sorts of interesting characters. And way too much going on to begin to recount it all. Drums, dancing. Acting. Flag-spinning. A guy on stilts. I got a sunburn.

The tables are turned….this guy saw me snapping him snapping me and started laughing, then came over and asked to take some together.

I couldn’t resist the urge to collect lots of sounds and pictures, so I’ll post more later, along with a (slightly) more in-depth look at the significance of some of aspects of this festival and Ghanaian festivals in general.

This week has been all about getting acquainted. My small room in a Soviet-era hostel (dorm) is becoming my home, albeit a temporary one. (I was told that we’d be moving to “renovated” rooms in an identical Soviet-era building across a small field this week. When they told me that, I mentally doubled it.) I’m getting to know the University of Ghana campus. All the places to eat. My department. The other Rotary Scholars. The ropes.

All the campus buildings are this lovely combination of white walls and red tile roof. They almost all have courtyards to allow the breeze to move through the rooms. There are (very red) dirt footpaths everywhere, and all kinds of gorgeous tropical trees.

There are people - mostly women - selling food around campus. This woman is carrying a tray of bananas (on her head, naturally.) Today I finally learned why the women selling bananas also sell little bags of nuts. They're peanuts. You get the bag of peanuts, tear it open, put a few in your mouth and then take a bite of banana. Voila! Peanut and banana! Possibly the best mid-morning snack I've ever had.

A home for people and a home for insects. I am not screwing with the perspective here. These are giant. And they're everywhere.

About those ropes. Large institutions invariably have systems and bureaucracies that are apparently inscrutable to outsiders trying to navigate them, but whose members – the insiders – seem to feel are obvious, intuitive, self-evident. And immutable. The University of Ghana is no exception. Let’s take as an example the passport photo. Now I’m no stranger to the passport photo. I don’t use it frequently, but I did apply for a new passport this spring. And I’ve applied for visas now and then. But here the passport photo reigns supreme. You need one for everything. Want to register? You need a passport photo for that. (Actually, international graduate students need at least three to register: One for the International Programs Office. One for the School of Research and Graduate Studies. And one for your department.) Trying to audit a course in another department? You need a passport photo for that. Looking to get permission to use the library? You need a passport photo for that. Signing up for a student organization? Hand over a passport photo.

The passport photo thing is only the amusing tip of a tangled bureaucratic mess of an iceberg. (How’s that for a mixed metaphor!) I spent the first few days of the week worrying about making sure I’d filled out the proper forms and given the proper documents – and photos – to all the proper people. I ran between departments, asking questions, collecting forms, with mounting frustration. Then, thwarted again and again, I finally accepted the inevitable. I may never know, exactly, if I’m registered for classes. Or how to check out a book in the library. Or whether and when the Grad Student Association is meeting. And I will have to give out a million copies of my passport photo.

My department, though, is lovely. Regina, another of the Rotary Ambassadorial Scholars, and I are both in the M.A. program at the Institute of African Studies. There are somewhere between twelve and sixteen students in our class. (I don’t know the exact number because, apparently, the first week is sort of optional.) Except for Regina and I, they’re all Ghanaians, and they’re a smart, interesting group.

Particularly interesting is Nana, a career broadcast journalist who is also a Queenmother, which an important role in Ghana tribal life. (That’s about the extent of my knowledge about Queenmothers so far; I’ll report back when I learn more.) She wants to research the role of these women in using their power to create social change. More about her later.

Already people’s personalities and roles are emerging, and yesterday we got into a great – and heated – discussion with one of our professors about school fees. While I was staging a personal rebellion against passport photos, some Ghanaian students have been protesting hikes in tuition and fees at the University of Ghana. Maybe there are more important things in life than passport photos…

I have my preferences, personally. It’s been a week, and I’ve sampled a few of the local dishes. Perhaps the most well-known is fufu (FOO-foo). Fufu is ubiquitous in West Africa; it’s a staple starch that’s often eaten with stew. It’s made with boiled cassava and plantains that are pounded. And pounded. And pounded. And pounded. Until they form a cohesive, gelatinous mass. I got to witness this process, at the home of a friend of Theo’s, Barbara.

Pounding fufu is a delicate dance. He lifts up the stick while she turns the ball of fufu in the bowl. She moves her hand away, he slams down the business end of the stick. This all happens amazingly fast.

When it’s judged sufficiently smooth and sticky, the fufu is formed into neat little balls that, traditionally, are plunked right into the stew.

You break off a small piece of the fufu ball with the fingertips of your right hand (only eating with your right hand is very important in traditional homes) and make a hole in it with your thumb. You now have a fufu spoon! Scoop up the broth, break off a bit of meat, and enjoy.

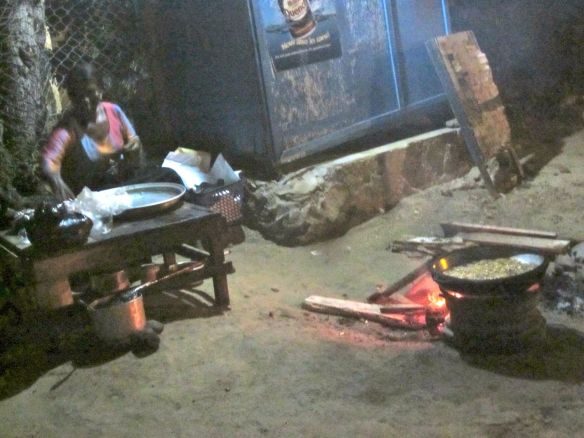

That soup was spicy! The food was all cooked outdoors in a wonderful outdoor kitchen. Outdoor kitchens keep it from getting too hot inside the house, of course, and they're also a really nice place for the family to hang out while the meal is being prepared.

Barbara was really nice about the fact that I couldn’t make it through that huge bowl. Theo kept telling me sternly that it was very rude not to eat all or nearly all of the food given to you in a traditional home. It was only my third day! I could barely eat toast yet. Soon I’m sure I’ll be plowing through fufu like there’s no tomorrow.

We’d originally stopped by Barbara’s house to pick up some plantains leftover from the funeral. (It was Barbara’s mother-in-law who passed away last week.) Barbara’s daughter thought it would be funny if she took fashion shots of me carrying plantains on my head. Carrying things on your head – lots of them – is a way of life here.

On to KENKEY… After my fufu adventure, I think Theo was a bit wary about giving me a whole plate of wonderful food to ruin. So the next day she ordered some fish and kenkey (KEHN-kay) and let me try it. Though I found fufu difficult, kenkey was a breeze. It’s made with ground corn meal. It’s pounded, but not for as long as fufu, so it has a grainer texture, similar to maza, which is used in Mexican cooking, and which I’ve have plenty of the in the States.

And finally, BANKU…. Last night, I got to try banku (BAHN-koo). I was nervous about banku, because like fufu, it’s pounded until it can be formed into a sticky ball. But like kenkey, it is apparently made with corn meal, and typically also plantains. The corn meal is allowed to ferment a bit, which gives it a mildly sour flavor. Banku is usually served with soup, stew or pepper sauce and fish. We – Regina and I – had it with fish. Really really good fish.

The little balls wrapped in plastic are banku. You can see the fish at the top, served whole with a generous portion of spicy pepper sauce.

Regina is one of the other Americans here on the Rotary Ambassadorial scholarship. She’s friends with a professor in the College of Public Health, who brought us to this awesome “joint” for dinner.

So now I’ve tried all three staple starches: fufu, banku and kenkey. Banku and kenkey are definitely my favorites, but fufu is unavoidable here, so I’m sure I’ll acquire a palate for it. Eventually.

One of the other culinary highlights from my week was grilled corn. I moved to campus in Legon on Thursday, and have been exploring the food options available…

And then there are plantains. Fried plantains. They are so, so, SO delicious. And one variation, kelewele (KELLY-welly), is particularly dangerous. Kelewele is a spicy, deep-fried version of fried plantains. Rotarian President Ben gave me a tour of Tema the night before I moved to Legon, and we finished off the evening with a visit to local kelewele shop.

The kelewele is frying in the pot in the right corner, while the lady who runs the shop is packing up orders that have been allowed to cool slightly.

Later, more on beans, fruit, jollof rice, plantain chips, milo, and the sweetest pineapple on the planet….and hopefully I’ll soon get to try the fabled groundnut stew.

It’s only my second day in Ghana, and already I’ve attended a funeral.

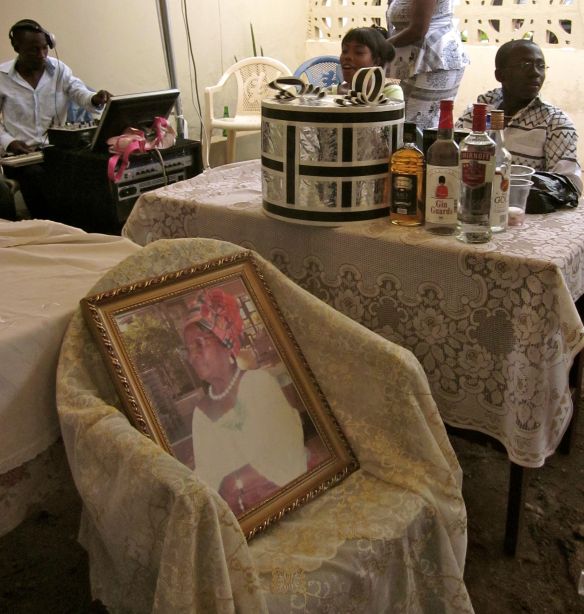

Right at the entrance to the family's compound, there was a photo of the deceased lady on a lace-draped chair. Typically people bring gifts or money to help the family cover funeral expenses (see the gift table). Note the DJ in the upper left corner of the photo.

There was a DJ and dancing. Laughing. Gifts and soda and beer given out by the family of the bereaved. Theodora, my host counselor from the Tema Rotary Club, brought me with her to a friend’s mother-in-law’s funeral in Adenta, a suburb of Accra. She explained that this is what happens on the third day of a funeral (usually a Sunday). The week before, the family buys creams and perfumes to anoint the deceased’s body, then stay awake all night with them. On Friday, there is a wake. On Saturday, the burial. On Sunday, after church, everyone dresses up in white (usually white with black accents), heads over to the house of the bereaved, and dances.

“It is to show the family that life goes on,” Theo told me. “We wipe our tears and dance.”

[dancing video]

Actually, I’d heard of this tradition before. Last spring, CIVIC had 12 African ladies come and visit. One was from Ghana, and I told her I was applying for a fellowship to study there. I remember it clearly; we were in Alan and Mary Brody’s beautiful home, feasting (Mary, too, is from Ghana). “You must go to a funeral!” this woman had said.

I asked Theo if they always wore these clothes to funerals, the white with black details. She said that only on Sunday, the day of dancing. On Friday and Saturday, they wear all black. And even then, white is only worn for those who had lived into old age. This woman, Nancy Maamle Ntreh, lived until 83; I now have a key ring with her photo and name on it as well as her age at the time she passed, a gift given to all the guests to remember her by. Theo told me that when people live this long, it is considered a blessing, so they wear white with black trim on this day. When someone young dies, though, only black is worn. One exception to both these rules is the death of a twin. “To have one baby is considered a miracle and a blessing,” she said. “To have two is doubly so, incredibly miraculous, the greatest gift.” So, she said, they wear all white, even the headdress, because the very existence of a twin is something so miraculous it must be celebrated and not mourned.

Before this foray, I spent most of the day recovering (i.e. sleeping). Theo picked me up at the airport yesterday, after more or less twenty hours of travel. (Hell, I think, resembles a night spent on a transatlantic flight.) She took me to small, quiet hotel in Tema (it’s owned by a Rotary member). The President of the Tema Club, Ben, came to greet me, and then left me to get some much-needed rest. Rtn. Pres. Ben invited me to come to church with him this morning, but I couldn’t drag myself out of bed after my long long long travels. (Rtn. Pres is short for Rotarian President; titles are important here, though they’re used with first names, not last.) Churches are incredibly important social organizers here, and already nearly everyone I’ve exchanged more than a few words with has asked me what church I go to. (“Catholic,” I tell them, though the answer is more complicated than that, as it is for many Americans.) And Christianity seems to permeate everything. On the road today, I saw churches everywhere. And I began to notice that many of the small shops on the side of the road have biblically-inspired names, many of them strikingly creative: “Ark of Noah Motor Repair,” “God First Upholstery,” “Do Good Radiator Specialist,” “Divine Grace General Store,” and my favorite, “All Power Belong to God Water” on the back of a water-carrying truck.

There are a lot of radiator repair specialists in the Accra area, and car repairmen in general. They're cheap and ingenious. I have no idea what's going on with the fire in the background...

The radio, too, is filled with Christian talk shows, though not the kind you’ll find in the U.S. On Theo’s radio on the drive back this evening, the radio host and his guest, a reverend, were discussing the topic of tolerance. They got into something of a debate on domestic violence and divorce. And then they started on homosexuality. Divorce according to reverend, was permissible, even desirable under some circumstances. Homosexuality, he maintained, was not to be tolerated. I’m sure that’s not the end of the story on those hot-button issues, but there you have my introduction to the moral politics of Ghana.

Theo drove me down the beach road in the darkness. The street vendors and music from places like the “Special Relaxing Spot” gave way to the shoreline. Waves of the same Atlantic Ocean I swam in in North Carolina this summer curling onto the shore. I felt terribly homesick last night, alone and exhausted and coughing hard, unable to sleep. The day with Theo awakened my curiosity, my excitement about learning as much as I can about this place, my enthusiasm for building relationships with them. Already, Theo is calling me her daughter, one of the girls who works at the hotel introduced me to one of the other staff as her “beautiful twin sister.” And the ocean in the darkness further eased my sadness at being again so far from home.